For some people, waking up every day means the start of persistent pain that affects their mood, thinking and relationships. This experience is more difficult when the pain doesn’t seem to have a cause; at least not a visible one.

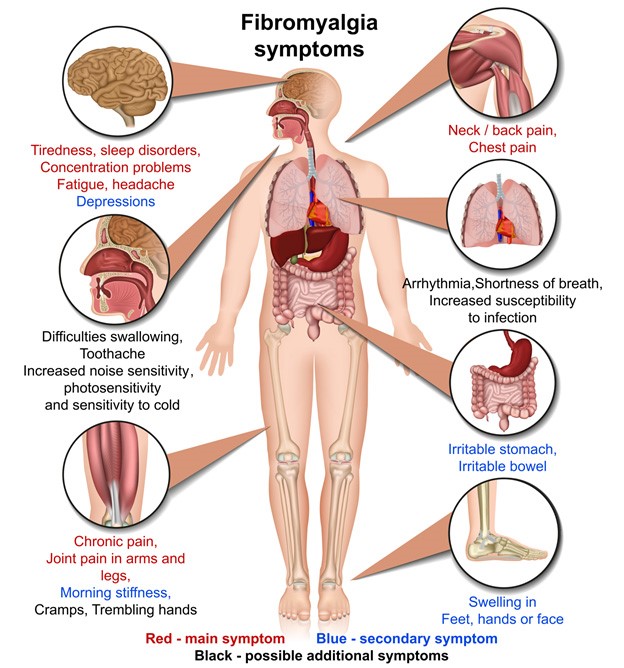

That’s the reality for people with fibromyalgia, a chronic disorder characterised by pain and muscle tenderness throughout the body where even the slightest touch can be sensitive. Sufferers often have other health issues, including sleep difficulties and fatigue.

For a long time, fibromyalgia was thought of as a medical mystery. Technological advancement has allowed us to look closer. Today, it is a recognised disorder, part of a group of chronic pain syndromes described as central nervous system disorders.

The condition affects more than four times as many women as it does men. With as many as 2-5% of the developed world living with fibromyalgia, it is far from uncommon. Yet targeted and effective treatment options aren’t available for the condition. And compared to fibromyalgia’s impact, this area of research remains highly underfunded.

Chicken or egg?

Fibromyalgia has a long history of stigma. Some explanations even pinned it down to being psychosomatic, “made up” and “all in your head”, as well as a condition people needed to “just get over”.

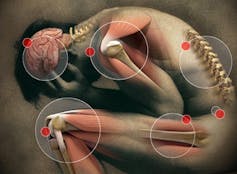

There may be some truth in saying fibromyalgia is “all in your head”, but more as a reflection of associated brain changes than a figment of the imagination. An explosion of recent research has shown brains of fibromyalgia sufferers are made up differently. There are variations, for instance, in regions key to how we think and feel.

Although our understanding has taken a dramatic leap in the last few decades, we can’t shut the book on fibromyalgia’s exact cause or causes. The reported brain changes pose a real chicken and egg scenario: are these brain changes causing fibromyalgia, or is fibromyalgia causing the brain changes?

The condition may have multiple causes. Some suggest biological factors, including a genetic basis for the disorder. Other research shows a history of sexual, emotional and physical abuse among sufferers. Psychological factors, including responses to chronic stress, have also been shown to contribute to its cause.

None of these are likely to be independent of each other.

Links to mood disorders

Further complicating explanations of fibromyalgia include its link to other illnesses, such as mood disorders like depression. This relationship likely reflects the fact they share some of the same biological processes, such as inflammation.

Inflammation occurs when injury or infection triggers the production of messenger molecules that flood to the site of injury as part of an immune response. It is now believed that, like injury to the body, psychological adversity and mental illness can trigger the same immune response affecting the brain.

And recent research suggests the occurrence of fibromyalgia or depression may increase the likelihood of the other. Regardless of what came first, though, the presence of mood disorders in fibromyalgia is linked to more pain and reduced quality of life.

It comes as no surprise, then, that if medical professionals and scientists can’t explain what causes fibromyalgia, it is even harder for the person living with the condition. In fact, those diagnosed have a significantly harder time understanding or explaining their pain to people with other disorders, like arthritis for instance.

Treatment options

It can take years to receive a fibromyalgia diagnosis, and some may have been misdiagnosed with one or more other conditions beforehand. This can be very frustrating for the patient as well as their doctor.

Currently, the best method of diagnosis is classification-based. Physicians assess the number of possible body areas where someone experienced pain in the last two weeks, and the severity of other symptoms, including fatigue and cognitive function.

Following diagnosis, there is no universally effective treatment plan. It usually includes a multi-method pain management regime from a team of health care providers. But responses to treatments can be no better than chance, regardless of whether these are pharmacological or others such as acupuncture or hypnotherapy.

Despite the poor response rate, pharmaceutical methods are the main treatment option. Prescriptions are commonly made out for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen), opioid analgesics (such as codeine), antidepressants, or anticonvulsants (drugs used to control seizures that also affect pain signals).

Because there is no clear treatment target for fibromyalgia, drug doses needed to manage symptoms have significant side effects. These include problems with thinking, drowsiness and the risk of drug dependency.

We don’t know exactly what causes fibromyalgia, but treatments need to be developed based on what we do know. For instance, we know there are brain changes. One promising treatment may therefore be brain stimulation techniques like Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS); a non-invasive technique that can change the activity of neurons in the brain.

There is a clearly an urgent need to provide targeted and effective treatment options for fibromyalgia sufferers. Considering how far we have come in explaining the unexplained pain of the condition, there is real hope for the future.